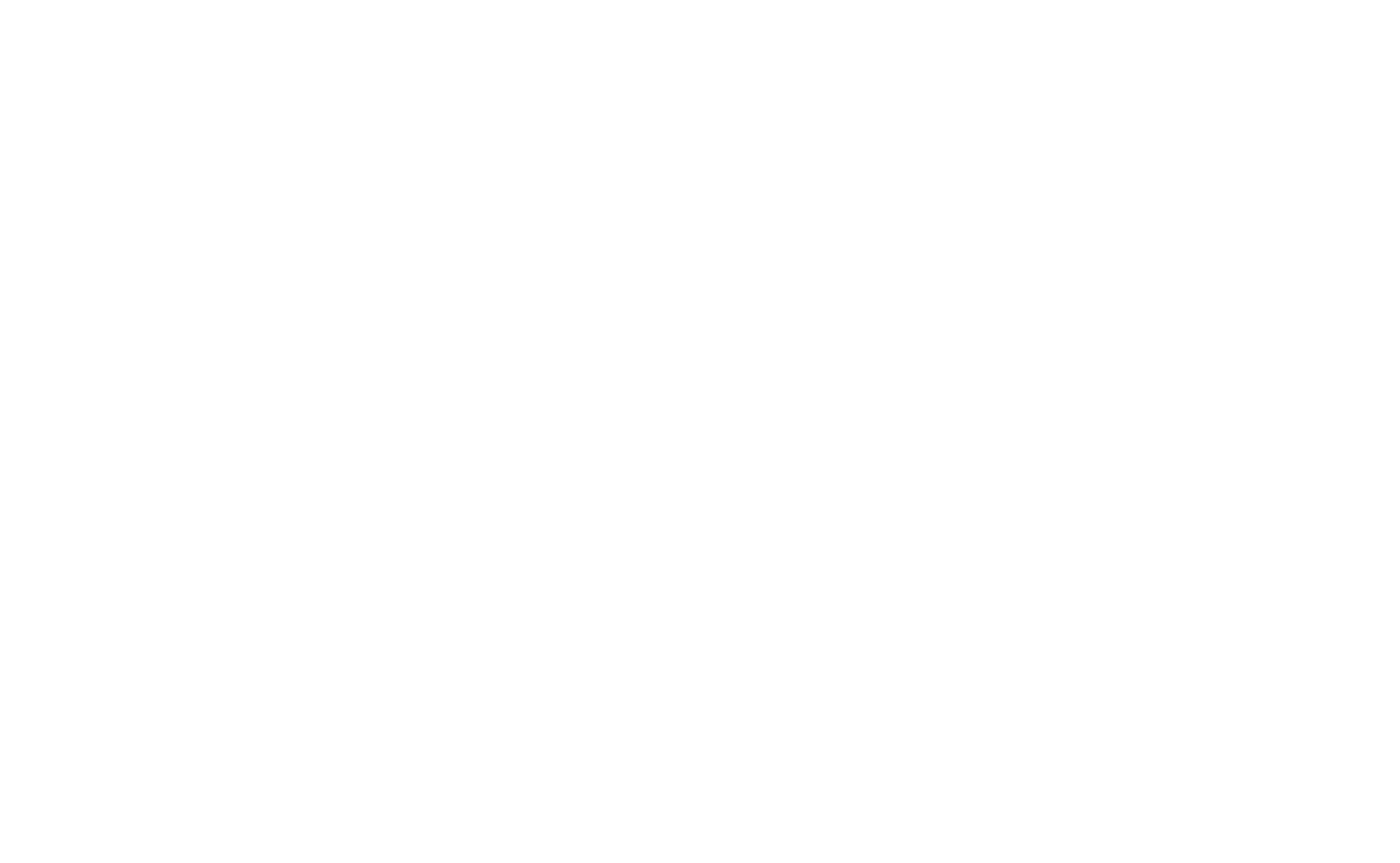

Book Review

Where William Styron’s 1990 memoir, Darkness Visible, served as a stark warning against the tranquilizers that deepened his depression, Ottessa Moshfegh’s My Year of Rest and Relaxation offers a radical antithesis. Her protagonist doesn’t flee from chemical oblivion; she sprints toward it. Set in Manhattan in the year 2000, this is the story of a young, recently orphaned narrator who decides the only cure for her existential malaise is to sleep for a year, convinced she will awaken reborn.

A common critique leveled against the novel is the narrator’s profound unlikeability. She is indeed acerbic, and her internal takedowns of her best friend, Reva—a bulimic, status-conscious striver who seems drawn from the pages of Bridget Jones’s Diary—are relentlessly cruel. But to dismiss the narrator as merely unlikable is to miss the point. Moshfegh skillfully balances this venom with a palpable, relatable despair, as when she confesses a desperate holiday wish: “that when I put my key in the door, it would magically open into a different apartment, a different life.” She is adrift in what Styron called a “dank joylessness,” a “poisonous fogbank” that leaves little room for kindness.

Her contempt for the world extends from her personal life to her professional one. The art gallery where she works is “all just canned counterculture crap, punk but with money.” Her hibernation is made possible by the brilliantly rendered Dr. Tuttle, a wildly unethical psychiatrist, but it’s facilitated by a controversial artist, Ping Xi. In a final act of cynical detachment, she allows him to document her oblivion as an art piece. Moshfegh’s sharp, vivid descriptions—the “dried-out sheet cake with finger gouges in it,” the tattered lace of Dr. Tuttle’s nightgown—compound this sense of decay. The world is ugly and disappointing; oblivion seems a reasonable alternative.

Ultimately, the cure for the narrator is not the Infermiterol-induced sleep itself, nor the art Ping Xi produces from it, but what Styron also found healed him: “seclusion and time.” As her year of rest concludes, she observes the simple beauty of the natural world and realizes, “Pain is not the only touchstone for growth.”

This personal awakening, however, is immediately juxtaposed with a collective nightmare. Her drugged year ends just before the tragedy of 9/11, and the novel’s challenging conclusion sees her swapping old movies for news footage of the falling towers. Moshfegh leaves us with a deeply unsettling question: what does it mean to find beauty and a reason to live in the stark finality of real-world catastrophe? It is a stark and powerful ending to a striking, adroit, and precisely rendered book.

0 Comments