TikTok’s a goldmine for Amazon shopping blunder videos. People order stuff without a care, and then, surprise! You just spent a hundred dollars on a doll’s chair when you thought you were buying something for humans to sit on.

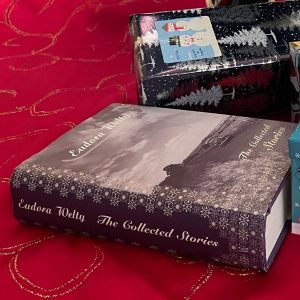

Here’s my literary version. I had casually tossed Eudora Welty The Collected Stories onto this year’s Christmas Amazon wishlist, thinking it would be a cozy, curated little sampling of Southern stories. My favorite writer, Ann Patchett, gushes so much about Welty’s talent, I wanted to get a taste beyond what I’d read in anthologies in college.

Buyer Beware

I didn’t bother to inspect the fine print. So when my wonderful sister gifted me the book, it turned out to be a whopping 622-page literary brick, containing four separate short story collections and two additional stories. This thing could moonlight as a dumbbell! It aligns more with the anthology genre than a book intended for continuous reading.

Never one to back down from a challenge, I decided to read the damn thing from start to finish. No reading it in parts, as I assumed it wouldn’t come back to it. Three weeks later, I turned the final page. Here’s what I thought of my unintentional Eudora Welty short story binge.

Overall Impressions

Eudora Welty The Collected Stories is one big dose of literary jambalaya, a mix of everything from comedy to tragedy, all seasoned with a heaping helping of Southern spice and lots of time for navel-gazing. It’s one heck of a ride through the Deep South of olden times with side trips to San Francisco, New York, Ancient Greece, and Europe. The stories were written between the 1930s and mid-1960s and contain negative depictions and mistreatment of people or cultures, and use of racist language and phonetic dialogue.

Eudora Welty The Collected Stories is one big dose of literary jambalaya, a mix of everything from comedy to tragedy, all seasoned with a heaping helping of Southern spice and lots of time for navel-gazing. It’s one heck of a ride through the Deep South of olden times with side trips to San Francisco, New York, Ancient Greece, and Europe. The stories were written between the 1930s and mid-1960s and contain negative depictions and mistreatment of people or cultures, and use of racist language and phonetic dialogue.

Eudora Welty, much like Ann Patchett, is quite the maestro when it comes to capturing life’s little quirks in her writing. Both sprinkle that special writer’s fairy dust that sucks you right into their fictional worlds.

However, Eudora’s storytelling takes a distinct turn down the time-travel lane. Her narratives are deeply immersed in the raw ambiance of the 1930s-1960s, resembling a well-preserved time capsule that can, at its best, transport you back in time. At its worst, though, it serves as a stark and discomforting reminder of the prevalent racist and sexist attitudes that persisted not too long ago.

Her characters, on the other hand, are nothing short of intense, occasionally veering off into the realm of eccentricity and, dare I say, the derangement zone.

But here’s the twist: sometimes, it feels like you’re watching sunlight shine through a tree instead of a story unfolding. I had my notepad out, jotting down notes like “not much happens” more times than I care to admit. Those super introspective, dialogue-light stories? They weren’t exactly my cup of sweet tea.

But don’t get me wrong; there’s a lot to appreciate in Welty’s writing. In that sea of “not much happening,” I managed to find plenty to admire.

To truly appreciate this collection, it’s best to delve into each section individually. So, let’s dive in and explore the compelling world of Eudora Welty’s storytelling.

A Curtain of Green and Other Stories (1941)

Let’s kick off with the first story, “Lily Daw and the Three Ladies,” a promising and lively start in which the dialogue zips faster than a mosquito dodging a swatter. It’s about three busybodies trying to ship Lily Daw off to the Ellisville Institute for the Feebleminded of Mississippi (this really existed), but plot twist: the xylophone player Lily met at a tent show the night before makes good on his promise to marry her. It’s like the church ladies and Aunt Bea from The Andy Griffith Show got their own episode. A good start.

Let’s kick off with the first story, “Lily Daw and the Three Ladies,” a promising and lively start in which the dialogue zips faster than a mosquito dodging a swatter. It’s about three busybodies trying to ship Lily Daw off to the Ellisville Institute for the Feebleminded of Mississippi (this really existed), but plot twist: the xylophone player Lily met at a tent show the night before makes good on his promise to marry her. It’s like the church ladies and Aunt Bea from The Andy Griffith Show got their own episode. A good start.

Now, let’s dive into “A Piece of News.” Brace yourself for the thrilling action: a young wife twiddles her thumbs at home, waiting for her husband, and leafing through a newspaper. Lo and behold, there’s a story about a woman with the exact same name as hers getting shot in a different town. What does she do? Spend her time fantasizing about her own demise, then her husband comes home and she tells him about it. A real adrenaline pumper, right? Okay, moving on.

“The Petrified Man” gets us back to a more lively place. In this story, a hairdresser regales her client with stories about her friend Mrs. Pike, who ultimately helps catch a criminal disguised as a nonmoving man at the “traveling freak show.” It’s rambling fun like an amateur true crime podcast, except with more hairspray and less “please subscribe to our channel.” I’m interested again.

And then “The Key” killed all my momentum. Deaf couple Albert and Ellie are waiting for a train to Niagara Falls. Albert finds a key dropped by a fellow passenger and pockets it, imbuing it without all his hopes and dreams for the future. “How terrible it was, how strange, that Albert loved the key more than he loved Ellie!” Lines like that made me roll my eyes. If there was symbolism here, I just didn’t get it and the whole thing felt like a literary version of a classic sitcom mix-up, where everything could be easily cleared up if someone just said something, but no one does.

In “Keela, The Outcast Indian Maiden,” we meet Little Lee Roy, an elderly Black man with a rather unusual backstory. As a child, he was thrust into a bizarre gig, playing a fake feral child in a red dress who chowed down on raw chickens in a “traveling freak show.” Fortunately, his stint in the peculiar world of sideshows came to an end when a kind stranger rescued him. The twist here is that the story unfolds from Little Lee Roy’s perspective, but he doesn’t say much. Instead, his tale is relayed by two white men chatting in his yard. And when Little Lee Roy does speak, brace yourself for some rather dated and offensive phonetic dialogue. The story does maintain an uplifting feeling as Little Lee Roy is vastly entertained by this blast from the past. And every parent can relate to the ending, when Little Lee Roy tries to tell his uninterested kids and grandkids about the encounter and they tell him to “Hush up, Pappy.”

Then I came to “Why I Live at the P.O.” and I was back in love with Welty. This story is basically a sitcom pilot waiting to happen. A woman has enough of her kooky family and moves into the post office. Kind of like The Simpsons, if Lisa left to live at school. Or maybe that episode where she gets a restraining order against Bart. Onward!

In “The Whistle,” we find ourselves in the company of a destitute sharecropping couple, both in their fifties, jolted awake by a chilling whistle signaling an impending frost. In a desperate bid to save their precious tomato crop, they sacrifice their bedclothes. But here’s the real kicker – they end up burning their furniture to stave off the cold in their home, doing so with a sense of reckless abandon. This story is a minimalist masterpiece with a mere two words of dialogue: the wife’s “Jason” and the husband’s “Listen.” It may not strike a chord of relatability, but it reads more like a morality play, illustrating the stark reality of people so impoverished that they must prioritize tomatoes over their own comfort, health, and safety.

“The Hitch-Hikers” is a road trip gone wrong, with a side of murder and a dollop of “what just happened?” It’s like if a car salesman accidentally stumbled into a Quentin Tarantino film. Most of the action happens off the page and we see the aftermath.

“A Memory” is basically this collection’s pause button. Nothing happens, but hey, sometimes you need a break from all the action to watch paint dry—or in this case, watch a lake lap the shore and think about a boy you like.

“Clytie” is a Southern Gothic soap opera crammed into a short story. You’ve got your decaying house, your extremely eccentric sister, alcoholic brother, dying father and a tragic rain barrel incident. It’s like “Days of Our Lives” with more rain and less resurrections. LOVED it.

“Clytie” is a Southern Gothic soap opera crammed into a short story. You’ve got your decaying house, your extremely eccentric sister, alcoholic brother, dying father and a tragic rain barrel incident. It’s like “Days of Our Lives” with more rain and less resurrections. LOVED it.

In “Old Mr. Marblehead,” we’re introduced to a polygamist with a peculiar desire: he’s low-key hoping to get busted by one of his two identical sons from different mothers. Welty starts by giving us an outsider’s view, painting a picture of his life as observed by nosy neighbors. But as the story unfolds, we’re granted access to his internal turmoil and chaos. It’s an engaging narrative but not written for humor.

“Flowers for Marjorie” immerses us in a bizarre and dark tale. It revolves around a young, jobless husband whose mental state hangs in the balance. In a shocking turn of events, he commits a heinous act, fatally stabbing his pregnant wife. This story stands out as one of the five in the entire book not set in the South, but rather in the heart of the Depression-era New York City. Its blend of confusion, oddity, and darkness creates a compelling narrative that diverges from the Southern backdrop prevalent in the collection.

“A Curtain of Green” unveils the journey of a young widow grappling with the aftermath of her husband’s tragic demise. Her quest for solace leads her to contemplate violence within the confines of her garden, haunted by the memory of the tree that claimed her husband’s life as she helplessly looked on. As a gardener, I dug this story.

“A Visit of Charity” is about a Campfire Girl who learns that old ladies can be scarier than any campfire tale. It’s a blend of “Are You Afraid of the Dark?” and a guilt trip for not visiting your grandma more often.

“Death of a Traveling Salesman” follows the unfortunate journey of a traveling shoe salesman who finds himself in a remote rural area, suffering a heart attack. As he receives aid from a couple he encounters, he ultimately meets his end inside his car. Amidst the isolation of his final moments, he grapples with a deep sense of loneliness and regret for not forging more meaningful human connections during his lifetime.

“Powerhouse” is a jazz-infused narrative that takes a dissonant turn when a Black musician receives a telegram from his wife’s lover, bearing the news of her demise. The story incorporates jazz slang, which can be challenging to decipher and at times may verge on being offensive. The Atlantic Magazine published this story in June 1941 and called it “unforgettable” but I found the slang and characterizations made by a white writer cringe-y.

Finally, we reach “The Worn Path.” This touching and poignant story revolves around a resilient Black grandmother who, despite her own health issues, embarks on a long and arduous journey along ‘the worn path.’ Her mission is to secure medicine for her grandson, who suffers from chronic respiratory problems due to ingesting lye. The narrative skillfully evokes a sense of place, delivering a well-executed and emotionally resonant tale.

The sense of accomplishment is high! Onward to the second collection, but a warning. I didn’t like it as much as the first. It wound up being my least favorite.

The Wide Net and Other Stories (1943)

Starting with “First Love,” we’ve got a deaf orphaned boy living out a Charles Dickens life in a hotel storage room in 1807, eavesdropping on the secret pow-wows of Aaron Burr and Harman Blennerhassett. Who, you ask? Exactly. Welty skips the history lesson, and we’re left Googling these guys instead of enjoying the story. (Burr is the U.S. Vice President who got Blennerhassett to fund an unsuccessful rebellion to turn the Western U.S. into a new country, if you’re wondering). Spoiler alert: the boy leaves when Burr does and we last see him wandering the frozen Natchez Trace in search of who knows what. This one bored me, I must admit. Plus I had to take time out of my reading to figure out what these historical characters were up to.

Starting with “First Love,” we’ve got a deaf orphaned boy living out a Charles Dickens life in a hotel storage room in 1807, eavesdropping on the secret pow-wows of Aaron Burr and Harman Blennerhassett. Who, you ask? Exactly. Welty skips the history lesson, and we’re left Googling these guys instead of enjoying the story. (Burr is the U.S. Vice President who got Blennerhassett to fund an unsuccessful rebellion to turn the Western U.S. into a new country, if you’re wondering). Spoiler alert: the boy leaves when Burr does and we last see him wandering the frozen Natchez Trace in search of who knows what. This one bored me, I must admit. Plus I had to take time out of my reading to figure out what these historical characters were up to.

Then there’s “The Wide Net,” a charming little ditty about a guy whose wife fakes a river dive. Hubby and the townies turn the search party into a fishing trip, only to find the Mrs. at home listening to radio soap operas or binge-knitting or whatever women did for fun in the 1940s. The best parts of this story are the nature depictions and the quirky characters who come along to drag the lake.

“A Still Moment” is a creepy story about a preacher who rides along through the Natchez Trace with a murderer and a naturalist who shoots birds so he can draw them. Believe it or not the naturalist comes off as the creepiest one here, because you expect him to be the kind person and he’s not really. The whole story carries a sense of terrible foreboding and is a suspenseful, not relaxing, read.

And then there’s “Asphodel,” which, thank goodness, saves the day by actually being easy to read and entertaining. It’s got a picnic, a ruined house, and a juicy tale of revenge that’s hotter than a Mississippi summer. Three women spill the tea on their friend Miss Sabina, who served up some serious “hell hath no fury like a woman scorned” vibes to her ex, and it’s deliciously dark.

“The Winds” blows in with a storm of confusion, following a young girl who’s a bit obsessed with an older girl named Cornella. It’s like trying to read someone’s dream diary—fascinating, but you’re not quite sure what’s going on, and you’re pretty sure the dreamer doesn’t either. Evocative of Virginia Woolf’s writing.

“Kin” is a delightful and poignant tale that delves into the intricacies of family bonds. The story revolves around a cousin’s return to Mississippi from the East to visit her family. It’s a heartwarming and humorous exploration of the ties that bind relatives together. Two cousins, Dicey and Kate, pay a visit to their elderly uncle who is suffering from dementia, and Sister Anne, another cousin who cares for him. The plot takes an amusing turn when Sister Anne rents out the parlor to a traveling photographer for the day. Dicey and Kate mistakenly interpret the gathering as a funeral, believing that Uncle Felix has passed away, but he hasn’t. The narrative beautifully intertwines memories and the way we perceive places from our childhood when revisiting them as adults. It’s a touching exploration of the enduring connections within a family.

“Kin” is a delightful and poignant tale that delves into the intricacies of family bonds. The story revolves around a cousin’s return to Mississippi from the East to visit her family. It’s a heartwarming and humorous exploration of the ties that bind relatives together. Two cousins, Dicey and Kate, pay a visit to their elderly uncle who is suffering from dementia, and Sister Anne, another cousin who cares for him. The plot takes an amusing turn when Sister Anne rents out the parlor to a traveling photographer for the day. Dicey and Kate mistakenly interpret the gathering as a funeral, believing that Uncle Felix has passed away, but he hasn’t. The narrative beautifully intertwines memories and the way we perceive places from our childhood when revisiting them as adults. It’s a touching exploration of the enduring connections within a family.

“Going to Naples” embarks on a journey with a mother and her youngest daughter as they travel from New York to Italy to visit family. Along the way, the daughter forms a romantic connection with a young cellist on the boat. This narrative skillfully captures the essence of strangers coming together during a shared journey, reminiscent of “The Bride of the Innisfallen,” but with a more coherent and engaging plot. The story explores themes of a daughter’s budding romance and a mother’s aspirations for her child, making it an enjoyable read. It’s a tale that resonates with the complexities of love and family.

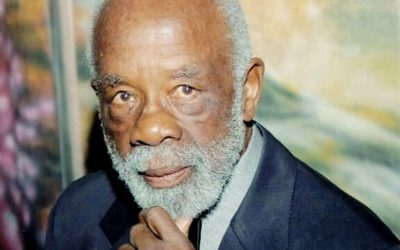

Uncollected Stories

In “Where is This Voice Coming From?” Eudora Welty deploys her empathy to look at the perspective of the type of man she believed to be responsible for the shooting of Medgar Evers, a prominent civil rights leader, in Jackson in 1963. She explains in the preface that she felt compelled to set aside other projects and write this story in a single night after Evers death, and it was soon thereafter published in The New Yorker. While the narrative paints an unvarnished portrait of a racist individual, some readers might find that it doesn’t offer much new insight into such attitudes. It serves as a stark reminder of the deeply entrenched racism that existed during that era.

In “Where is This Voice Coming From?” Eudora Welty deploys her empathy to look at the perspective of the type of man she believed to be responsible for the shooting of Medgar Evers, a prominent civil rights leader, in Jackson in 1963. She explains in the preface that she felt compelled to set aside other projects and write this story in a single night after Evers death, and it was soon thereafter published in The New Yorker. While the narrative paints an unvarnished portrait of a racist individual, some readers might find that it doesn’t offer much new insight into such attitudes. It serves as a stark reminder of the deeply entrenched racism that existed during that era.

“The Demonstrators,” the final story in this vast tome, follows a white doctor as he attends to two Black victims involved in a domestic dispute during one fateful night. The narrative provides insight into the turbulent atmosphere of change prevalent in Mississippi during the 1960s. However, some readers may find a concerning aspect in the portrayal of the two Black characters as having killed each other in a domestic altercation, particularly when viewed through the lens of a white doctor. The story also delves into the doctor’s personal struggles, including his failed marriage and his wife’s animosity towards him, particularly when he questions the truthfulness of civil rights demonstrators who claim they were forced to pick cotton in the scorching June sun, despite cotton not being grown in June. While the narrative offers a glimpse of the era, it may not resonate with everyone or significantly deepen their understanding of the complex dynamics of that time.

The Sum of It All

In retrospect, discovering Eudora Welty’s ‘Collected Stories’ was akin to receiving an unexpected gift that I somehow picked out for myself. It may have been a bigger challenge than I initially imagined, but I’m proud that I embarked on this literary journey. Welty’s stories held gems waiting to be uncovered. As I navigated the intricacies of her characters and settings, I found moments of sheer brilliance that made the journey worthwhile.

So, here’s to embracing the unexpected, even when it arrives in the form of a 622-page literary brick. In the end, Welty’s ‘Collected Stories’ proved to be an enriching experience, reminding me that sometimes, the most rewarding journeys are the ones we didn’t quite plan for.

Some have speculated that the story bears the influence of D.H. Lawrence in its exploration of disquieting notions about desire, and I’m inclined to agree—it certainly ventures into some unsettling territory.

Some have speculated that the story bears the influence of D.H. Lawrence in its exploration of disquieting notions about desire, and I’m inclined to agree—it certainly ventures into some unsettling territory. The Golden Apples is a short story cycle set in Mississippi in the fictional town of Morgana, comprising seven interrelated but narratively discontinuous stories. This was my favorite collection for its lighter tone and readability and most especially how beautifully she tied everything together in the final story, The Wanderers. And kudos to Welty for handing us a character list at the start, because without it, we’d be as lost as a left sock in a dryer.

The Golden Apples is a short story cycle set in Mississippi in the fictional town of Morgana, comprising seven interrelated but narratively discontinuous stories. This was my favorite collection for its lighter tone and readability and most especially how beautifully she tied everything together in the final story, The Wanderers. And kudos to Welty for handing us a character list at the start, because without it, we’d be as lost as a left sock in a dryer.

“No Place for You, My Love” opens “The Bride of the Innisfallen and Other Stories” with an engaging narrative. It follows the journey of a married man and woman who, temporarily estranged from their spouses, embark on an impromptu road trip to explore the southern landscape. Their adventure leads them to a quaint, run-down restaurant in a remote rural area, where they share a dance before returning to New Orleans. In truth, the story doesn’t offer many dramatic events; it’s more about the suspended anticipation, as if both characters are waiting for something significant that never quite materializes. However, Welty masterfully captures the essence of a specific time and place, immersing readers in the atmosphere of yearning. The tale delves into the intriguing dynamic between these two strangers, hinting at underlying sexual tension that never fully blooms into a physical encounter, not even a simple kiss.

“No Place for You, My Love” opens “The Bride of the Innisfallen and Other Stories” with an engaging narrative. It follows the journey of a married man and woman who, temporarily estranged from their spouses, embark on an impromptu road trip to explore the southern landscape. Their adventure leads them to a quaint, run-down restaurant in a remote rural area, where they share a dance before returning to New Orleans. In truth, the story doesn’t offer many dramatic events; it’s more about the suspended anticipation, as if both characters are waiting for something significant that never quite materializes. However, Welty masterfully captures the essence of a specific time and place, immersing readers in the atmosphere of yearning. The tale delves into the intriguing dynamic between these two strangers, hinting at underlying sexual tension that never fully blooms into a physical encounter, not even a simple kiss.

0 Comments