by Lynn Lipinski | Dec 10, 2013 | Personal, Profiles

I was born in 1969’s ‘summer of love’ and learned how to walk and throw tantrums while women across the United States read Betty Friedan and fought for equal pay for equal work, the right to practice law or sit on a jury. For little girls like me,...

by Lynn Lipinski | Feb 13, 2013 | Personal, Profiles

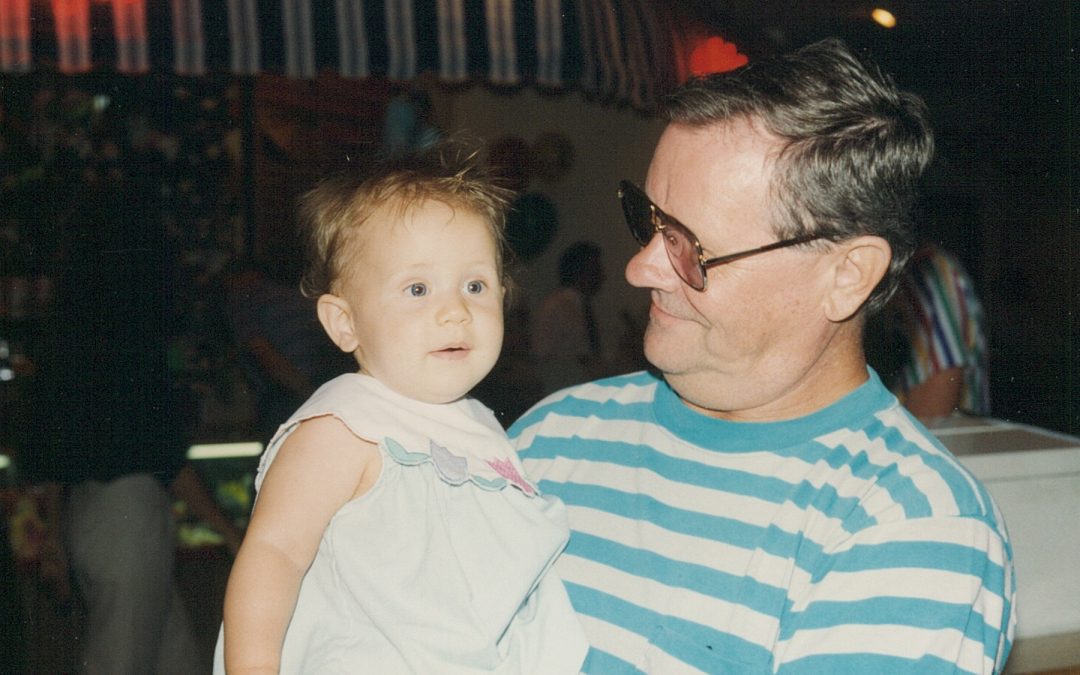

My father spent a lot of time staring at the ceiling in his last year of life. Parkinson Disease ravaged him from the inside out, shakes giving way to a terrible stiffness in his muscles. It was as though his spine was contracting, drawing the muscles and tendons and...