by Lynn Lipinski | Aug 22, 2021 | Essays and Features, Personal, Stories We Love, Writing

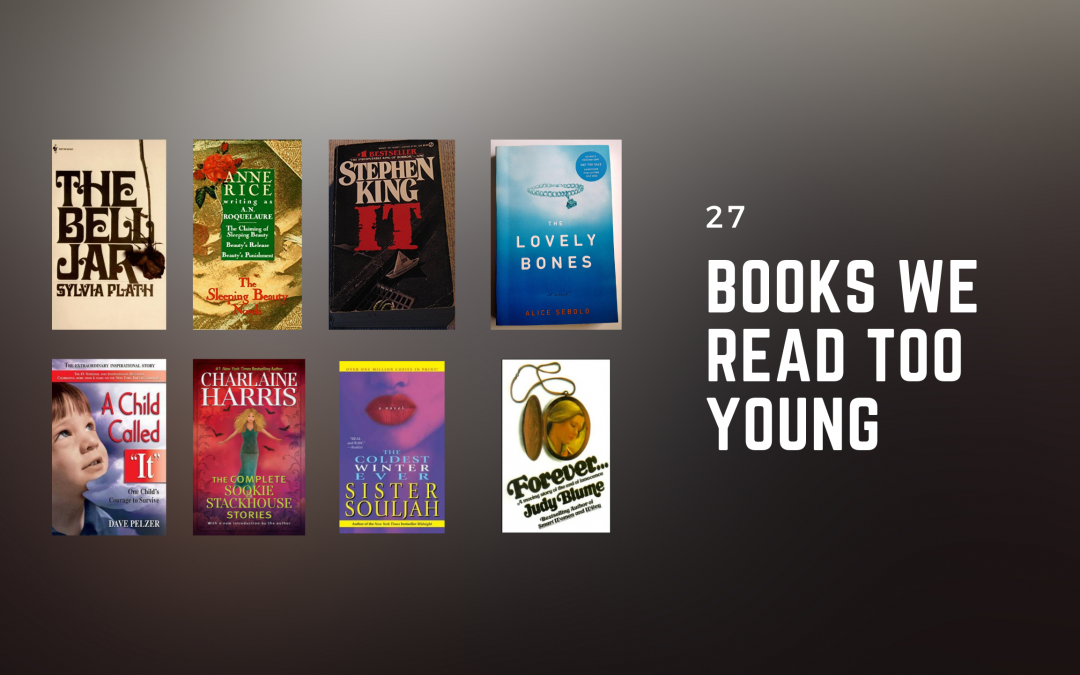

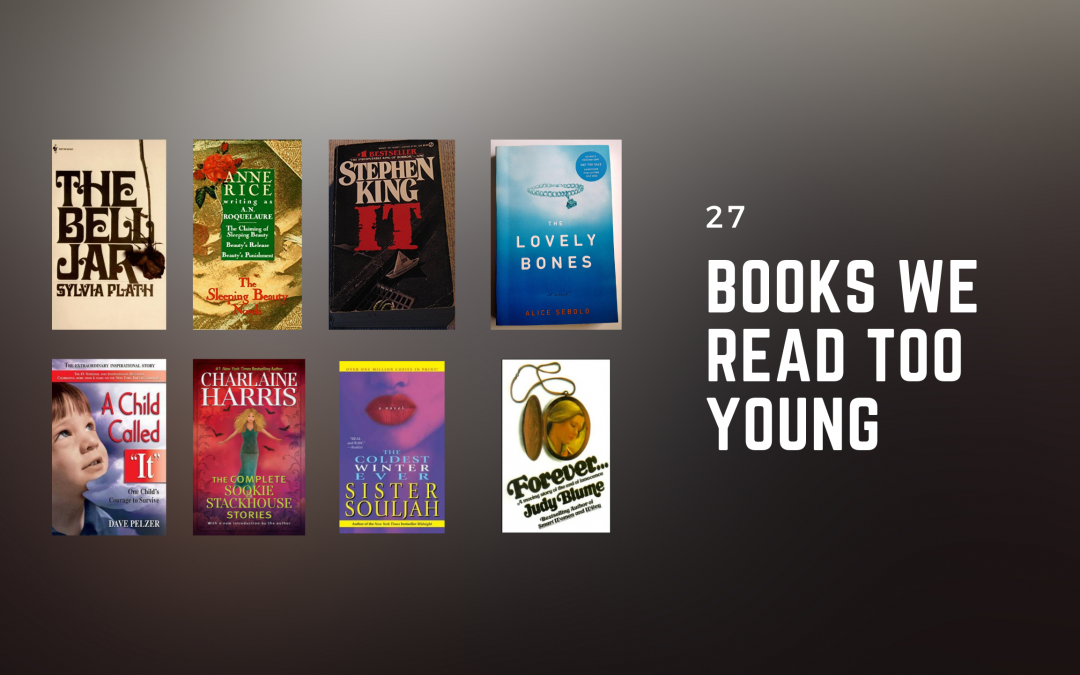

Which of these books did you sneak from the library or your parents’ bookshelf when you were way too young for it? If you were an avid and early reader like me, you powered through the kids and young adult book sections at the library fast and wandered over to...

by Lynn Lipinski | Feb 4, 2021 | Essays and Features, Personal

“Can you be Bananas the Monkey tomorrow?” I was seventeen years old, punching my time card as a waitress at Casa Bonita, a massive Disneylandish restaurant sitting behind a bright pink storefront in a strip mall near a wig store and a check cashing place....

by Lynn Lipinski | Sep 22, 2020 | Essays and Features, Personal

Depending on the light and my mood, the potted cacti and succulents on my front porch resemble either the strange skyline of a science fiction city or the motley cast of characters in Star Wars’ Chalmun’s Cantina. A tangle of golden snake cactus, the opuntia’s...

by Lynn Lipinski | Sep 15, 2020 | Essays and Features, Oklahoma, Personal, Unsolicited advice

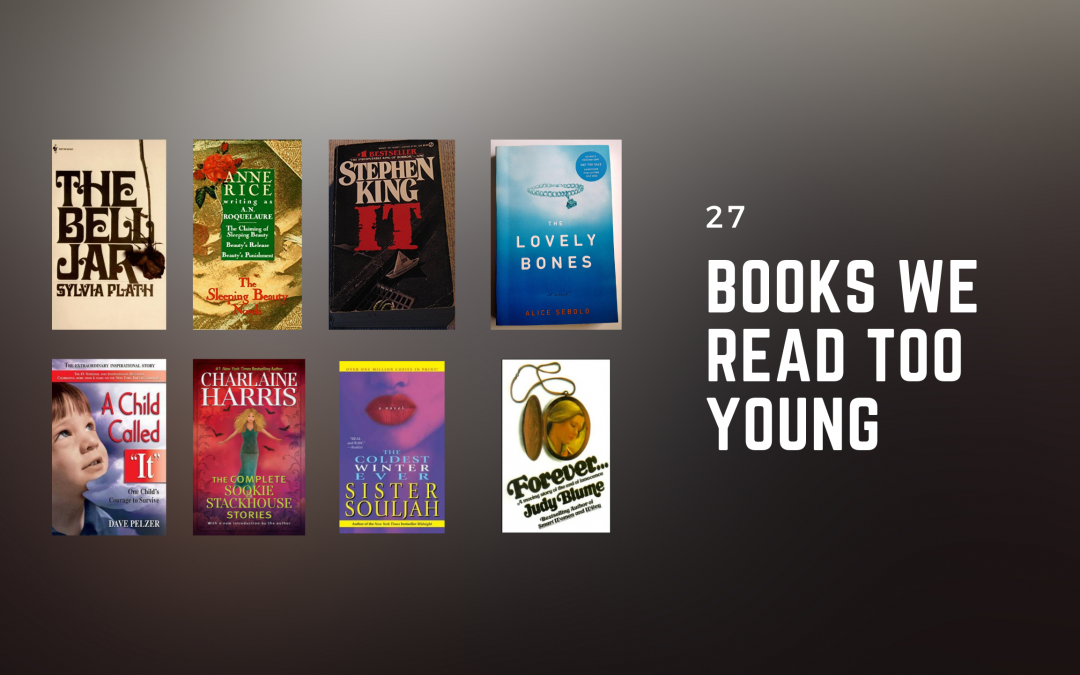

Summer camp is not just a rite of passage, but also a fine social experiment in making friends, overcoming homesickness and trying new things. A week at summer camp in Robber’s Cave State Park in Oklahoma’s Sans Bois Mountains when I was 12 brought me a...

by Lynn Lipinski | Sep 9, 2020 | Essays and Features, Oklahoma, Personal, Writing

The summer of my eighth birthday was overshadowed by a grisly crime made all the more harrowing because of its child victims. On a humid and rainy Sunday in June 1977, the idyllic memories of summer camp I had shared with my friends shattered into shards of horror...

by Lynn Lipinski | Aug 23, 2020 | Essays and Features, Los Angeles, Personal, Writing

In 1999, I landed a job that offered excellent medical benefits with one hitch: no dental coverage until after the first year. Perhaps I could go without dental benefits for one year? It seemed a calculated risk worth taking, my then-husband and I thought. We were...