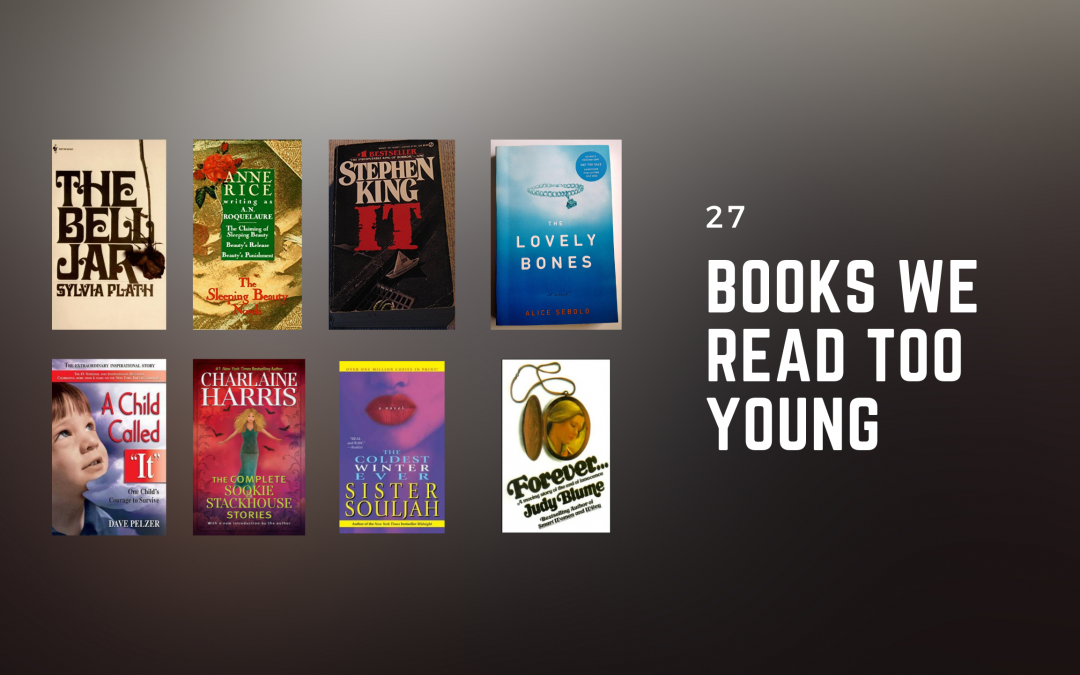

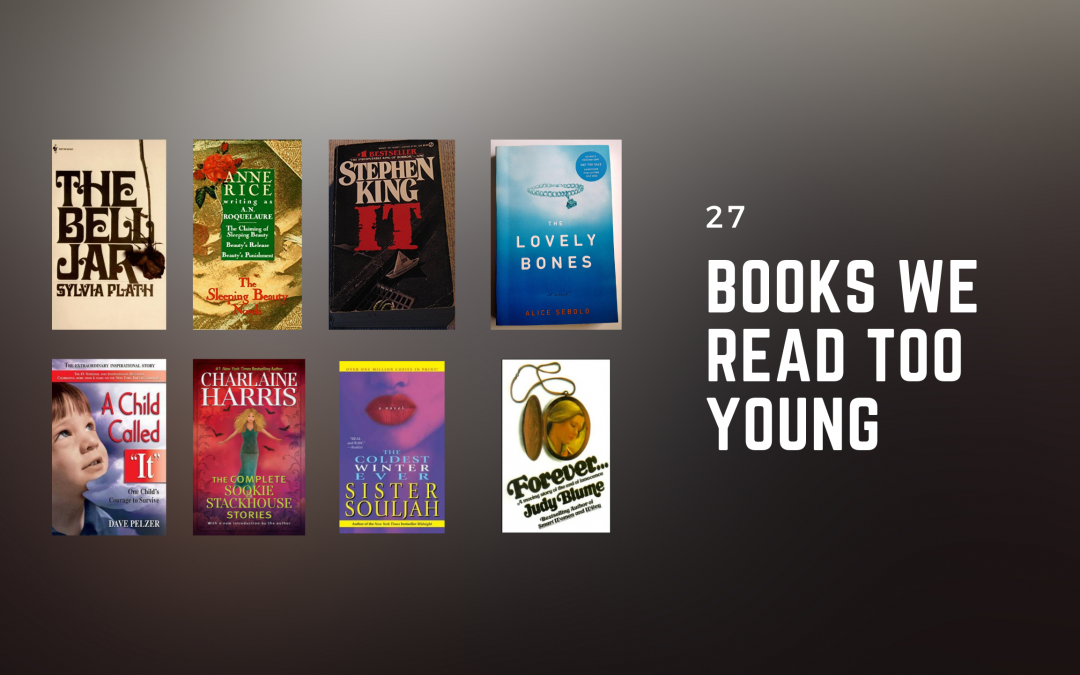

by Lynn Lipinski | Aug 22, 2021 | Essays and Features, Personal, Stories We Love, Writing

Which of these books did you sneak from the library or your parents’ bookshelf when you were way too young for it? If you were an avid and early reader like me, you powered through the kids and young adult book sections at the library fast and wandered over to...

by Lynn Lipinski | Sep 9, 2020 | Essays and Features, Oklahoma, Personal, Writing

The summer of my eighth birthday was overshadowed by a grisly crime made all the more harrowing because of its child victims. On a humid and rainy Sunday in June 1977, the idyllic memories of summer camp I had shared with my friends shattered into shards of horror...

by Lynn Lipinski | Aug 23, 2020 | Essays and Features, Los Angeles, Personal, Writing

In 1999, I landed a job that offered excellent medical benefits with one hitch: no dental coverage until after the first year. Perhaps I could go without dental benefits for one year? It seemed a calculated risk worth taking, my then-husband and I thought. We were...

by Lynn Lipinski | Feb 17, 2019 | Essays and Features, Writing

Who hasn’t heard about hackers ripping into a small-town water treatment system in Florida and altering the chemical supplies recently? It was an explosive news story laying bare the potential for hackers to poison a water supply. It caught our attention with...

by Lynn Lipinski | Dec 31, 2018 | Fiction, Oklahoma, Personal, Writing

The bones of the Bloodlines story rattled around in my head for nearly a decade. The main character, Zane Clearwater, was an intruder into my original story. He had a minor role as a love interest to another character. But as I wrote and rewrote the story and worked...

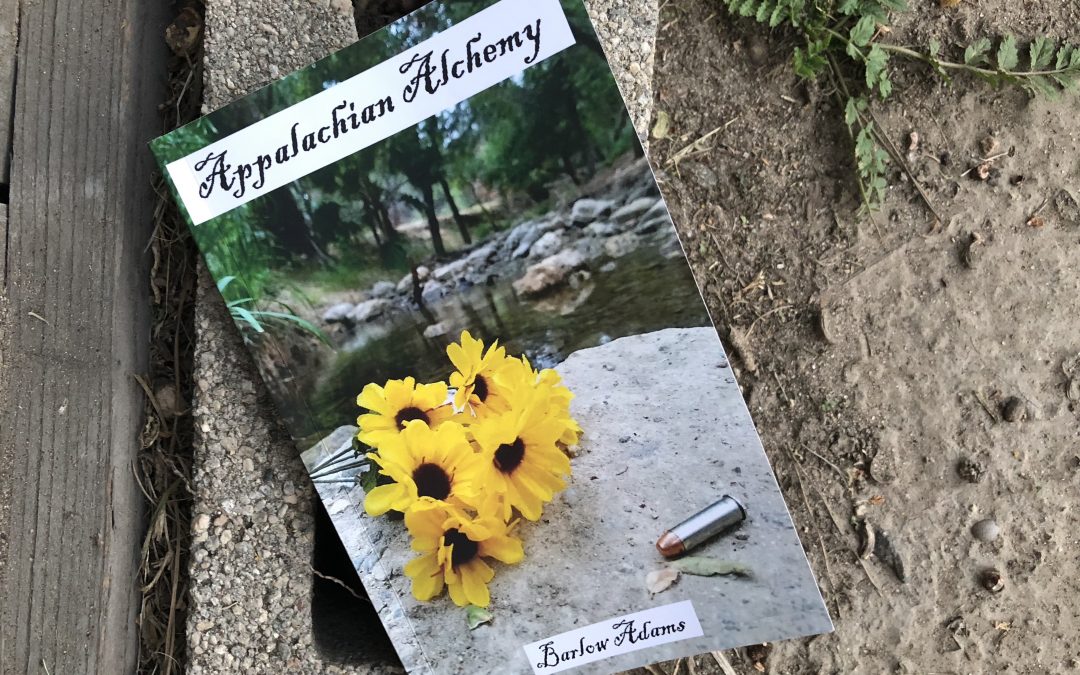

by Lynn Lipinski | Oct 5, 2018 | Fiction, Writing

This first appeared in Pine Mountain Sand & Gravel in October 2018. Are you made of lead or water? Will you sink, or will you flow? Life is rough on the banks of the Kentucky River in Barlow Adams’s debut novella, Appalachian Alchemy, which finds the youngest...