by Lynn Lipinski | Feb 4, 2021 | Essays and Features, Personal

“Can you be Bananas the Monkey tomorrow?” I was seventeen years old, punching my time card as a waitress at Casa Bonita, a massive Disneylandish restaurant sitting behind a bright pink storefront in a strip mall near a wig store and a check cashing place....

by Lynn Lipinski | Sep 15, 2020 | Essays and Features, Oklahoma, Personal, Unsolicited advice

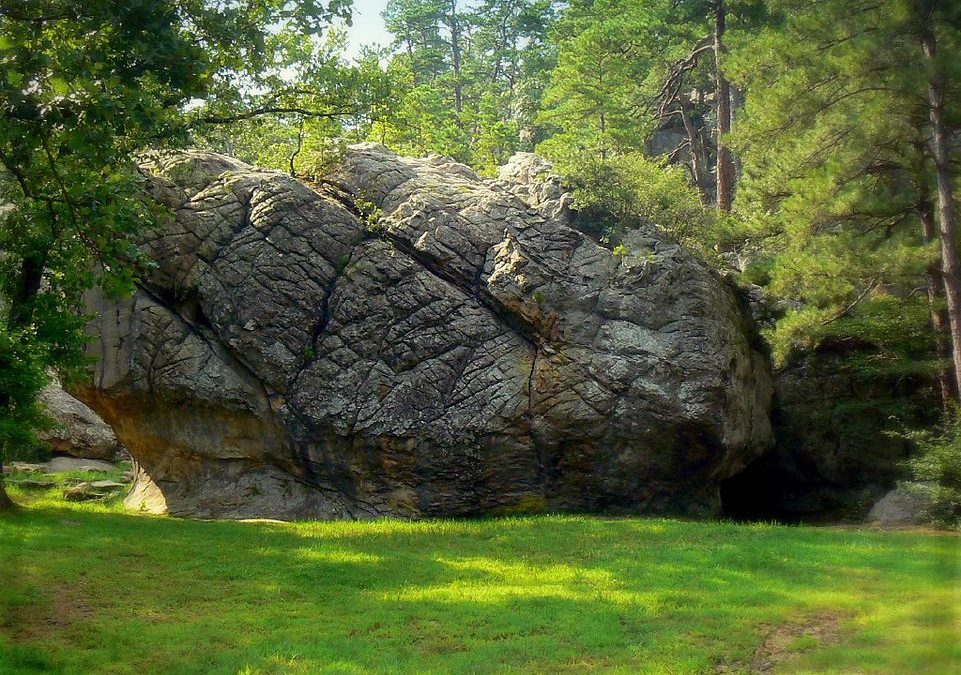

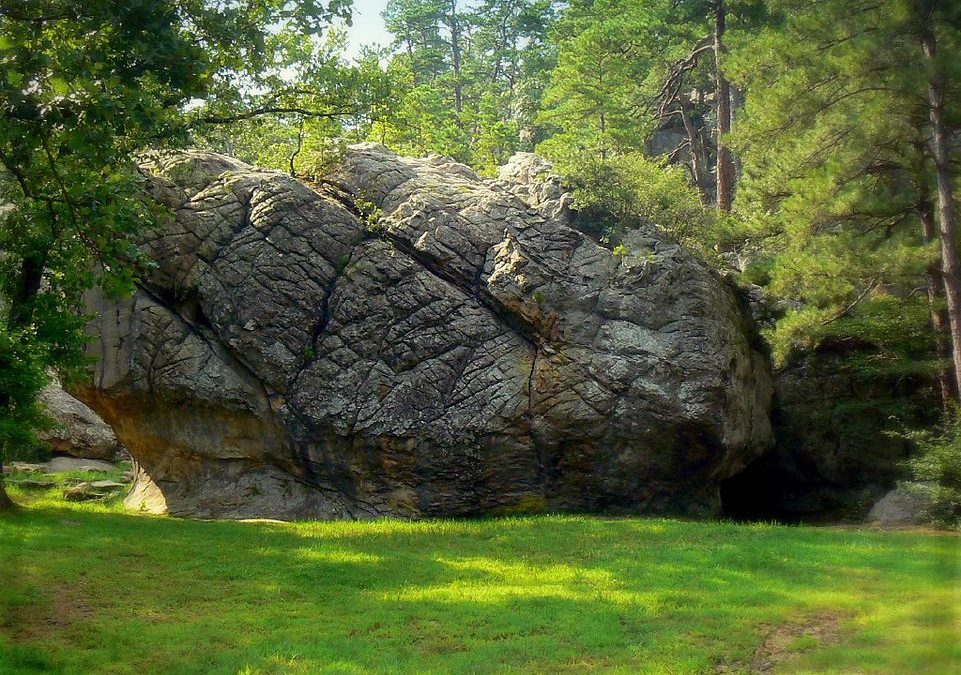

Summer camp is not just a rite of passage, but also a fine social experiment in making friends, overcoming homesickness and trying new things. A week at summer camp in Robber’s Cave State Park in Oklahoma’s Sans Bois Mountains when I was 12 brought me a...

by Lynn Lipinski | Sep 9, 2020 | Essays and Features, Oklahoma, Personal, Writing

The summer of my eighth birthday was overshadowed by a grisly crime made all the more harrowing because of its child victims. On a humid and rainy Sunday in June 1977, the idyllic memories of summer camp I had shared with my friends shattered into shards of horror...

by Lynn Lipinski | Feb 28, 2011 | Essays and Features, Personal

There’s nothing particularly fancy about a piece of satin-finished Frankoma pottery, made of creamy beige clay from the Arbuckle Mountains or reddish clay from Sugar Loaf Hill. But something about its blend of Western inspired lines and practicality appeal to...

by Lynn Lipinski | Jan 26, 2011 | Essays and Features, Oklahoma, Personal

It was the opposite of an Oklahoma land rush in Picher this week, as giant yellow CATs started knocking down abandoned homes and businesses in this town scarred by eight decades of mineral mining. Most of the town, including its multiple piles of discarded rock,...